I’m a long-time fan of games – card games, board games, and video games. I suppose this is an increasingly common thing as we live in a golden age for indie games. This is as true for board and card games as it is for video games. Recently, I began working on a game concept and design to simulate the ways human groups of differing social complexity might interact in time and space. Thus, Social Complexity: The Game was born.

It’s sort of a mash-up between Catan and the World Game. I am certainly not unique in this type of work; a good summary of similar (and more advanced) experiments with games and anthropological pedagogy can be found in the following blog posts by Krista Harper (Post 1 and Post 2).

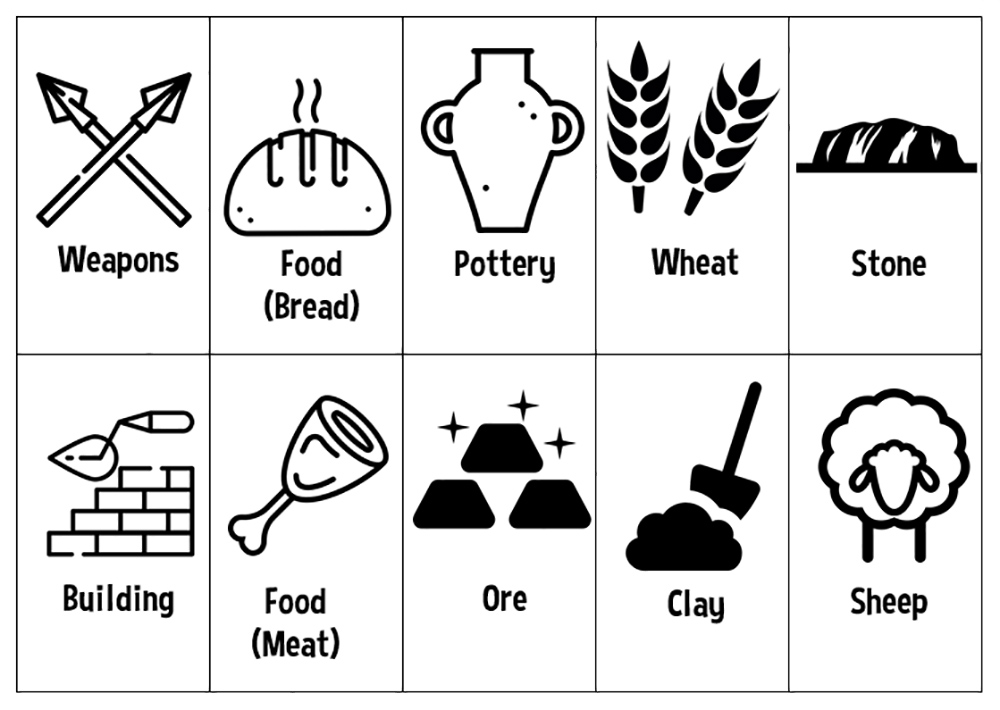

The basic premise of the game involves splitting the class into four groups corresponding to different degrees of social complexity. Each group begins with a stock of raw materials consisting of sheep, stone, wheat, clay, and ore. Groups then have to negotiate and interact with other groups to acquire additional raw materials and/or convert these materials into crafted products. Crafting converts raw materials into meat, bread, weapons, building materials, pots, and prestige items.

I chose pastoralists, horticulturalists, agriculturalists, and chiefdoms for the four groups. My decision was based on simulating the variety of groups that co-existed in many areas during or following the Neolithic Revolution. As such, each group has access to different resources, craft specialists, and the like. These resources are related to the population of each group.

Pastoralists (with a population of 50) begin the game with 20 sheep and 2 stones. To successfully finish the game they need 2 pots, 2 meat, 2 bread, 2 weapons, and 2 building cards. They must also maintain a herd of at least 10 sheep (10 sheep cards). Other groups start with different amounts of these and different resources. The chiefdom (with a population of 1,000) begins the game with 12 clay, 6 wheat, 6 stone, and 2 ore cards.

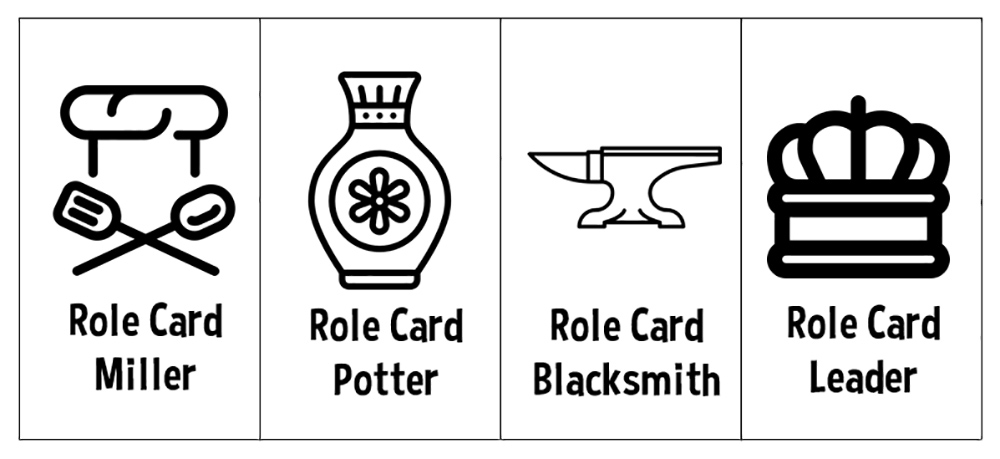

Complexity is added to the game with the introduction of roles representing craft specialists. Specialists are present in different groups. The Miller (who can turn wheat into bread) is present in the horticultural, agricultural, and chiefdom groups. The leader and blacksmith cards are reserved for the chiefdom group. In addition, certain groups have specific rules. The chiefdom must select a leader, and then the group must follow the decisions of the leader, reducing individual agency. The chiefdom groups is allowed to determine the selection process.

There are also rules for interactions between groups. If a group has wheat but no miller, they must barter/trade with a group that does have a miller. The group with the miller can turn the wheat into bread free of charge, or charge 0-2 raw material cards for the service. Of course, groups that charge too much may find themselves restricted from future trade deals.

Groups can coerce other groups into trade deals by stockpiling weapons. If a group has twice the number of weapons as another group, they can force the group to provide 2 raw materials or 4 crafted items. Since everyone can turn stone into weapons, small arms races can develop quickly. Groups can also coerce other groups to craft items. A group can only attempt to coerce another group once per turn. Coerced interactions can be countered. The mobile nature of pastoralists protects them, and ore can be crafted into prestige goods that will nullify an attempted coerced interaction.

Turns are called by the instructor. I have only tested the game once in my General Anthropology course (spring 2017). The majority of groups finished within 10-12 minutes of the end of class. However, if groups had finished earlier, I had a set of disasters (e.g., famine) that would have removed raw or crafted items from everyone’s inventory and restarted the trading cycle, effectively serving as a second round.

The first test went very well. Each of the four groups had 8-10 students. Some groups acted through consensus, while in others a strong-willed student took charge. The chiefdom had a clear leader, a female leader. We have discussed the existence of female leaders in prehistory several times, so this was not necessarily a surprise. The pastoralists were the first to amass weapons and attempt to coerce other groups. The agriculturalists raided the horticulturalists’ village (they found cards left on a student’s desk, I allowed it).

Most of the students spent the first few minutes introducing themselves and discussing strategies. I moved from group to group passing out new cards when crafting took place, and explaining real-world examples of things that were happening between the groups. Overall, I consider it a success and will continue to develop the game. I had a blast and students enjoyed it as well. I’m even thinking of a turning it into a board game. So, watch out for the home version of Social Complexity: The Game!

If you’re interested in trying the game out, send me an email. I’m happy to share it!