The use of digital technologies for visualizing past environments is experiencing something of a renaissance. This is due to dropping costs of hardware and an increase in the intuitive usability of 3D/virtual environments. The ability to deliver interactive content via the internet (a.k.a. Web 2.0) provides new ways of sharing research wider audiences. These developments also provide exciting pedagogical potentials. This post discusses how my teaching of historical archaeology benefits from these emerging technologies. Specifically, the use of a virtual world environment to explore historical architecture as described in James Deetz’s In Small Things Forgotten: An Archaeology of Early American Life.

Those familiar with Deetz’s text will recall how various chapters discuss how changes in different artifacts through time reveal changing culture patterns in American history. Chapter five, titled “I Would Have the Howse Stronge in Timber” focuses on changing house forms in the Mid-Atlantic and New England regions of colonial America.

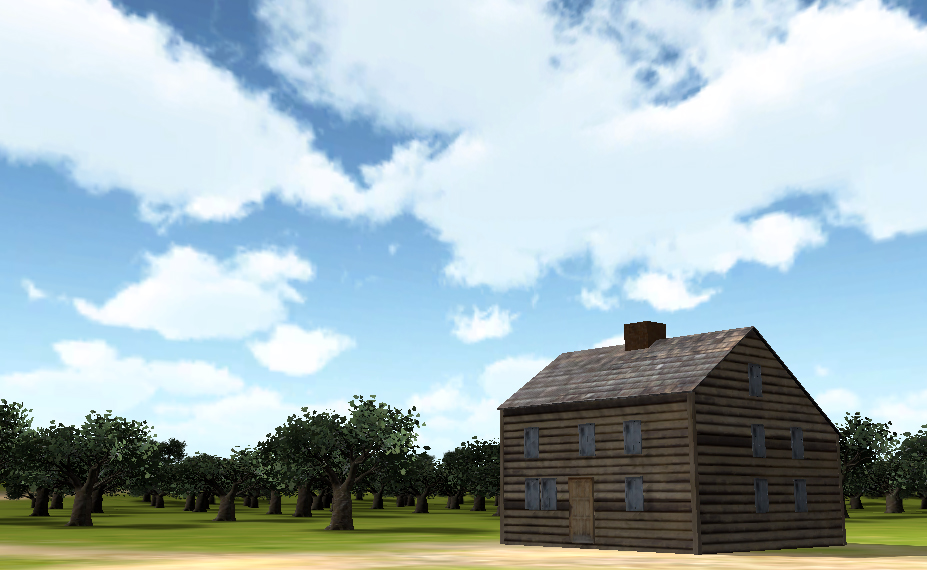

This chapter begins with a discussion of early 17th century house forms, including the saltbox, earthfast, and Chesapeake End Chimney houses. Examples of saltbox houses still exist while the other two have larger disappeared. The chapter includes an illustration of the first and third types, and an illustration of the earthfast construction technique occurs in chapter one.

The Chesapeake End Chimney house may be familiar to readers of the text because of its similarity to the house at Flowerdew Hundred. Less recognizable and more organic house forms also appeared at the time, including the Fairbanks House located in Dedham, Massachusetts. This unique structure, not illustrated in the text, dates to 1637 and is the oldest timber-frame house in North America.

Deetz goes on to explain the increasingly regional aspect of houses in the US by the late 17th century. These include the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony, Garrison Colonial, Rhode Island Stone Ender, and log houses. These structures drew upon English (or Swedish in the case of the log cabin) traditions but increasingly included new traits associated with a distinctly American style.

Deetz goes on to explore an increasingly American vernacular tradition in existence by the early 18th century. This includes the gradual disappearance of the Cross Passage Houses common during the 17th century alongside the development of new social relationships between servants and their masters. This house form is partly superseded by the Hall and Parlor House in New England and houses with end chimneys in the Mid-Atlantic.

A number of the structures discussed by Deetz either appear in other portions of the book or are not illustrated. In the past I have used images to discuss this chapter. Then, during the fall semester of 2013 I decided to experiment with 3D modeling the various structures using 3DS Max. After texturing the individual structures (ten in total) I imported them into the Unity3D game engine and created a virtual world.

This virtual world environment is available online. Instead of my traditional lecture showing images of the various house forms, I projected the virtual world environment and explored it with the class. I asked the class about each house and students responded with date ranges, geographic areas, and various other points.

While I regularly use virtual reconstructions of sites in my research and scholarship (e.g., Rosewood Heritage & VR Project), this was the first time I integrated it into my teaching. In doing so, I discovered a deeper appreciation for the material in Deetz’s book and the students appeared more engaged by this alternative format. The lecture took on a more playful tone and encouraged some of the quieter students to engage for the first time.

As always, thanks for reading and please feel free to contact me with any questions.

– Ed

P.S. The models and virtual world environment were constructed in less than 6 hours, before a 4:30pm course, so there is certainly room for improvement!